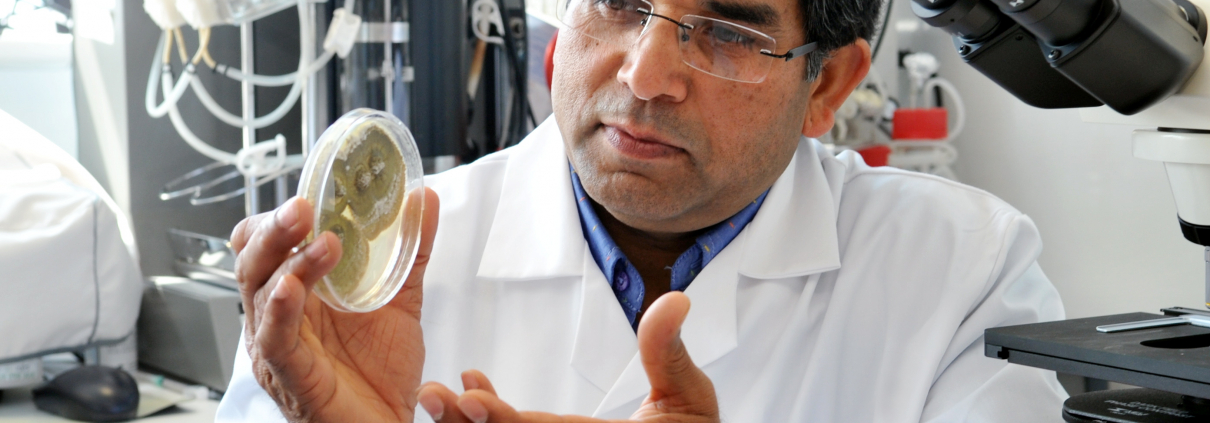

Dealing with global extremes: STRI’s head of sports surface technology, Dr Stephen Baker, considers the problems of turf management in some of the more extreme climates that he has visited in his 38-year career.

Working conditions

Grass selection and maintenance is very dependent on climate, and in many parts of the world there is not the relatively benign climate for turf grass growth that we experience in the United Kingdom.

Whilst there can be significant issues with snow and frost in the winter, average monthly temperatures in the UK typically range from around 0°C to 20°C and this is a relatively comfortable range for grass growth for most of the year.

Dealing with global extremes

Contrast this with some of the sixty countries that I have worked in. Parts of Russia or Scandinavia where the average minimum January temperature of -15°C to -20°C (and lows of -40°C) and average maximum monthly temperatures of 38°C to 43°C in India, Morocco and Saudi Arabia, with peak temperatures sometimes exceeding 50°C, made for some interesting working conditions.

Similarly, in the UK we have a relatively reliable rainfall and without the very high intensities experienced in some tropical areas.

Annual average rainfall in the UK typically ranges from around 700-1250mm per year for the more heavily populated parts of the country where most sports facilities are found.

In contrast annual rainfall can be as low as 100mm in Saudi Arabia. At the other extreme, average monthly totals can reach over 300mm in Manaus in the Amazon Basin in Brazil or in Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia and massive 840mm in Mumbai, India. It should be noted that these are just average values and at times the temperature range and rainfall differences can be much greater. It is inevitable that extreme variations in temperature and rainfall will increase the challenge of producing high quality sports surfaces.

Low temperatures

The map, above, shows the range of climates around the world from the perspective of turf management.

Each of the climate areas has a major influence on selection of the appropriate grass species in relation to the ideal temperature range. However, there is also a wide range of other issues such as drought and salinity tolerance, the sports to be played and the potential standard of maintenance, including irrigation demand.

Fortunately, a very wide range of grass species are available, and they can be split into two very different groups depending on their basic biology: the cool-season grasses and warm-season species. Cool-season grasses would include species such as smooth-stalked meadow-grass (Poa pratensis) and perennial ryegrass (Lolium perenne), which are used on areas of more intensively used turf such as football or rugby pitches, and finer fescue (Festuca spp.) or bent species (Agrostis spp.) that may be suitable on areas such as golf courses.

For areas of extremely low temperatures it is inevitable that appropriate cool-season grasses will be used, but there are several aspects of management that may need to be considered:

• Minimum temperatures that are likely to be encountered

• The length of the growing season, in particular how much of the playing season coincides with periods of minimum growth

• Duration of snow cover and the need for snow removal. Snow cover is indeed often used as an insulating blanket to protect the turf during the coldest months of the year, but there can be significant challenges in clearing the snow and making the surface ready for the start of the new playing season

• The potential risks for disease, especially under snow cover or during periods of limited growth

• The opportunities for pitch renovation. In the more extreme climates for example of North America, Scandinavia and Russia the main playing season will coincide with spring, summer and early autumn when growing conditions are generally better. However, this may limit the amount of time available for renovation, as for example end-ofseason work would coincide with lower temperatures thus preventing effective grass establishment

As well as selection of suitable grass types there are several management options that may improve the standard of turf in very cold climates.

Undersoil heating and pitch covers are generally essential for the major stadiums in such climate areas and, as latitude and cloud cover have a major influence on light levels, most stadiums in these colder climates would also need supplementary lighting to extend the period of grass growth.

Maintaining a high standard of grass cover can also be a big issue in these colder climates. Annual meadow-grass (Poa annua) is very well adapted to the colder, wetter climates such as Iceland or the west coast of Norway.

Without the possibility of extensive end of season renovation there are only limited opportunities to establish preferred species, so annual meadowgrass tends to increase rapidly with time. To maintain a reasonable balance of grass species there is a need for regular over sowing throughout the summer months, with ideally a break in the middle of the playing season to allow a short renovation window.

High temperatures

High temperatures cannot be isolated from rainfall and there tends to be two main extremes where high temperature and rainfall interact: (1) high temperature but low rainfall in desert or semi-arid environments, (2) high temperature, high rainfall areas, although these can have a distinct wet season and a dry season which will have a major impact on turf management. For the monsoon season in Mumbai, India, the four months between June and September have a combined average of about 2250mm rainfall, while the four months from January to April have a combined rainfall of less than 5mm.

The main factor influencing grass quality in hot climates with either low annual rainfall or seasonal drought, will be water supply through irrigation and a good quality irrigation supply will be essential. For high standard stadiums water will generally be delivered using an appropriate pop-up irrigation system, but for more general, lower maintenance areas techniques such as subsurface irrigation may also have to be considered to improve water conservation.

Grass selection is normally based on warm-season species such as bermudagrass (Cynodon spp.), seashore paspalum (Paspalum vaginatum) or various Zoysia species, but there may be other considerations.

Dealing with global extremes

In the absence of cloud cover, nighttime temperatures in some desert climates can be very low giving a risk of dormancy of the warm-season grass. In some wetter tropical climates, particularly where there is significant photochemical air pollution in major urban areas, light levels might be insufficient to maintain healthy grass growth at certain times of the year, especially in stadium environments.

A further factor compounding issues of heat stress in many of the drier climates is the quality of the irrigation water and the potential build-up of salts in the soil. Assessment of water sources for irrigation becomes a major item in turf design in such areas and regular excess irrigation may be needed to flush accumulated salts out of the rootzone.

Very hot, wet areas also have some very specific challenges: these include high intensity rainfall (which I’ll discuss later) but also high rates of biologically activity and this can have particular challenges with disease, insect pests and weed invasion.

Management of the turf in the hottest parts of the world must consider all these issues. There are however some management techniques that can also restrict temperature stress, including:

• air circulation systems by which cooler area can be pushed from lower in the soil profile to cool the grass at the surface

• syringing with light applications of irrigation water to dissipate heat by evaporation

• shade covers mounted well above the grass surface to restrict the incoming solar radiation

• installing cooling pipes, reversing the principle of undersoil heating.

Transition zones

Some of the biggest challenges with grass selection occur in transition zones where there are extreme ranges of temperature. These include Mediterranean type climates in parts of Europe, South America, South Africa and Australia but also some of the continental extremes, where winter temperatures can be as low as -30°C, while summer temperatures may hit 35°C.

Under these circumstances a single grass type is very unlikely to be able to tolerate the annual temperature range: warm-season grasses will go brown and dormant in the winter and cool-season grasses are likely to be lost to heat stress and disease in the summer period.

Good management is obviously essential in such climates, but inevitably more than one grass species will be required, with the warm-season grass used in the summer and then being oversown with a cool-season grass to give the colour and performance required for the winter months.

Rainfall

It is impossible to provide a good quality turf surface without adequate irrigation and issues of turf management in hot, dry climates have already been discussed above. However, there are methods to improve the water retention properties of sports turf rootzones using various organic and inorganic amendments. The type and concentration of these amendments is critical – too little amendment and the surface may remain dry and hard. Excess amendment can lead to a soft playing surface, with shallow rooting that is easily damaged by play. Laboratory testing and a very good understanding of requirements for the growing medium is essential to help formulate the most suitable rootzone characteristics for a specific climate zone.

Very high rainfall is also an issue, as most sports surfaces rely on a relatively dry, stable surface for optimum playing conditions. Well-constructed rootzones, usually based on a high percentage of a suitably selected sand, are generally essential to give adequate drainage performance.

However even a well-constructed rootzone with a drainage rate of say 150mm/hr will not be able to cope with the most extreme rainfall events. In such circumstances it may be necessary to construct a turf facility with greater slopes to encourage surface runoff of water.

Dealing with global extremes

Technology can also help – many of the subsurface air circulation systems used for temperature control can be used to generate sufficient suction within the soil to help remove extreme rainfall from the surface.

Wind

Excess wind may sound more like a complaint of the digestive system than a problem faced by most sports turf managers, however there can be situations where high winds (or indeed a lack of air movement) can be a factor in sports turf management.

Aside from destructive events such as hurricanes, the most likely problems of high wind would be on exposed sites where irrigation can be affected.

If there are strong prevailing or drying winds, evaporation rates are likely to be higher and therefore water consumption greater. However, it is the effects on water distribution that may be the greatest challenge, as the effect on the uniformity of water application can be significant.

This may necessitate changes in the basic design of the irrigation system with for example changes in the specification for the pop-up heads or sprinklers at closer spacings than on a less exposed site. It will also increase the need for careful monitoring to ensure that there are no dry areas that are being missed and for selective hand watering to supplement moisture levels on any drier areas.

Lack of significant air movement should also not be under-estimated. In modern stadium environments the surrounding stands may restrict air movement to the extent that drying of the surface is compromised and the risk of disease and surface algae may increase.

Where there is temperature stress this can be even more important, for example with cool-season grasses growing at times of elevated summer temperatures. Under these circumstances the use of fans around the pitch to help air movement can be a very important factor in reducing turf stress and sustaining a high-quality playing surface.

Modern sports turf management

In the last 40 years the range of available technology has expanded to an unbelievable extent. The understanding of turf construction and management principles has improved, by both technological innovation and research investment. More marginal climates that gave high levels of stress affecting grass development can now have much better-quality turf surfaces, provided that development projects are well designed and constructed and that there are sufficient levels of resources to deal with these climate extremes.